The Medicalization of Death and How to Reclaim a Better Way to Die

How science and spirituality intersect one of the most important things we will each face

Story at a Glance

Scott Adams, who recently passed from an aggressive, rapidly progressing prostate cancer, openly shared his final journey with a wide audience. Though his protracted suffering disturbed many, he approached the process in a wise and mature manner, offering valuable insights for others facing the dying experience.

Over centuries, the medical industry has increasingly monopolized death and dying, fostering a cultural view that treats death as something to fear, deny, and exclude from life—rather than a natural companion to accept.

This distortion makes dying far more arduous in our society, fueling an escalating medicalization of death in which expensive, often futile interventions are imposed on patients—frequently against their deepest values and wishes.

In contrast to the materialist scientific view that consciousness emerges solely from brain activity, compelling evidence indicates consciousness can persist independently of the brain and, in some cases, even transfer between individuals or contexts (e.g., via organ transplants or near-death accounts).

Recognizing the spiritual dimensions of dying—and how they intersect with modern medical discoveries—is vital for supporting a healthier, more meaningful transition. Many ancient and enduring traditions regard this moment as one of the most significant in human life.

This article explores practical strategies for facilitating an optimal dying process, drawing on shared wisdom from diverse historical and spiritual traditions while examining their alignment with contemporary medical sources.

Prior to the COVID-19 vaccines being released, many concerns were raised about these experimental gene therapies, including their potential for causing infertility, autoimmune diseases, and cancer (e.g., many of the theoretical autoimmune issues were summarized in this article Stefanie Seneff wrote shortly after the vaccines hit the market).

So, when Pfizer’s regulatory submission to Europe’s FDA (the EMA) was leaked on December 9, 2020, I read through it in detail and discovered that Pfizer simply had been allowed to exempt itself from testing the vaccine for these three key issues (despite that testing being required for gene therapies). Given that, I assumed that they had been tested for, major issues were found, and that Pfizer concluded their best option was to simply claim plausible deniability by insisting they “didn’t know” their vaccines would do all of that (because they’d “never” tested for them).

Note: the EMA publication also presciently highlighted other key issues with the vaccine such as regulators expecting it might not work in the field (due to the virus rapidly mutating), that the vaccine’s mRNA rapidly degraded, and that the lipid nanoparticles were chosen for efficacy rather than safety.

Regrettably, due to the religious fervor surrounding the vaccine (e.g., that it would rescue us from the lockdowns and return everything to normal), my arguments to wait on the vaccine largely fell on deaf ears with my colleagues and instead, excuse after excuse was made to dismiss the highly unusual and severe complications our patients kept developing immediately after vaccination (e.g., “there’s no evidence for this”).

Before long, people I knew around the country began contacting me with severe complications following the vaccination (e.g., dying suddenly or an elderly relative rapidly progressing into dementia) to ask if it could be linked to the vaccine. Hating that there was nothing at all I could do to stop this (I felt like an ant in front of a tsunami), I then decided I needed to document all of them so that I’d at least have some type of “evidence” I could show my skeptical colleagues (as I knew the medical journals would never allow vaccine injury datasets to be published).

In the process of doing that, I came across numerous cases of cancers rapidly developing (or dormant ones that had been in remission for years coming back) immediately following COVID vaccination, including numerous unusual cases which strongly argued the two were linked (e.g., a benign lump that had been stable for over a decade suddenly growing at a rapid rate after vaccination and being diagnosed as an extremely rare cancer they had no risk factors for which had metastasized throughout the body). Before long, more and more people noticed similar things, and the notion of COVID-19 “turbo cancers” entered the cultural lexicon. Since that time, the medical orthodoxy has denied this is an issue, but more and more datasets are emerging showing it is—which is particularly unfortunate, as beyond rapidly progressing, “turbo cancers” tend to be much less responsive to cancer treatments.

All of that briefly, is why I believe the medical field has irreversibly damaged the credibility it worked for decades to earn with the public.

Scott Adams

When Trump ran for office in 2016, initially very few people believed Trump could win (e.g., this was shown in the political betting markets). However, Dilbert’s author Scott Adams did, and rapidly built a large online following by highlighting how his training as a hypnotist allowed him to recognize that Trump was the most politically persuasive candidate and hence, Scott hypothesized, favored to win.

As such, once Trump won, Scott pivoted to using that same lens (how persuasion shapes political events) to become a pundit on a variety of other current issues. During that process, Scott Adams made the controversial decision early on to endorse the COVID vaccine to his followers and vaccinate and belittle followers who didn’t, leading to many derisively calling him “Clot Adams.”

Note: I know of multiple other instances where individuals who were long considered “experts in propaganda” made the decision to get the COVID vaccine—something which I view as a testament to how effectively the vaccine was marketed (and the fact that very few people, including “medical experts,” have an in-depth understanding of controversial medical topics).

Later, in January 2023, to his great credit, Scott posted a video admitting he was wrong and the anti-vaxxers were entirely correct. However, he framed the decision to not vaccinate as being due to one’s “luck” of habitually not trusting the government and that being correct in this one instance, rather than the correct decision being a result of intelligent reasoning, as “all” the data at the time had shown vaccination to be the correct choice and every intelligent person (Adams included) who correctly analyzed that data had concluded vaccinating was the proper choice.

Then, on May 19, 2025, Scott Adams disclosed to his audience that he had terminal metastatic prostate cancer, vulnerably shared he planned to utilize California’s medically assisted dying in the near future to reduce his suffering, and that he had no further interest in using fenbendazole or ivermectin for the cancer because he’d already tried them without success. This shook a lot of people up, in part because they had strong feelings about how cancer should be treated and in part because it being widely publicized online made a lot of people bear witness to a torturous and protracted death process and hence were forced to be present to the reality of the phenomenon in their own lives.

Scott eventually tried a variety of cutting-edge conventional therapies recommended by top oncologists, and among other things, had the Trump administration directly intervene on his behalf with Kaiser when his access to them got abruptly cut off (highlighting the challenges patients without connections routinely face in the medical system). Nonetheless, nothing worked, and he gradually became weaker and weaker until he said his final goodbyes to his followers and passed away at home on January 13, 2026.

Note: following this, I polled the audience here to find out if there was interest in discussing this topic, and found out a lot of you wanted this topic to be explored (e.g., due to the emergence of turbo cancers).

Changing Relations with Death

People are so afraid to die that they never begin to live—Henry Van Dyke (1852 – 1933)

In 1976, astute philosopher and polymath Ivan Illich published Medical Nemesis, which critiqued the medical system and predicted many of the issues which emerged in the decades that followed (e.g., he highlighted that since our society had conditioned us to believe that instead of relying upon ourselves, we always needed a doctor to get better if we were sick, it created an inexhaustible demand for medical services which would always increase but never be satisfied).

A key theme he covered in Chapter 5 (pages 64–77—which can be read here), was that through the medical profession’s marketing, our cultural conception of death evolved from an intimate, lifelong companion we had no separation from to a feared, medicalized entity to be conquered by doctors and Illich traced this shift through six historical stages, from the Renaissance “Danse Macabre” to modern death under intensive care, where death is defined by the cessation of brain waves.

Note: as I show here, that modern criterion for death is quite dubious and in part exists to support organ donations and eliminate the long term costs of treating vegetative patients.

Illich argued that this medicalization, driven by the medical profession’s growing control, stripped individuals of autonomy, turned death into a commodity, and reinforced social control through compulsory care. He also argued this Western death image had been exported globally, supplanting traditional dying practices and contributing to societal dysfunction by alienating people from their own mortality. I agree with him, but feel the impacts of this were far more profound than even Illich hinted at.

Medicalized Death

Presently, one of the most common settings for death in America is within the hospital. This however is controversial as:

End of life care is invasive and uncomfortable.

End of life care is frequently futile.

End of life care constitutes one of the largest medical expenses in the country.

Many individuals do not want to let their loved ones go and hence insist upon fighting for the care.

Restricting end of life care is seen as government choosing to execute people to save money.

Doctors who administer end of life care frequently refuse it for themselves.

For example, to quote a 2016 article in Time:

Doctors spend more of their lives in hospitals than anyone else. But when it comes to deciding where to die, they’re less likely than the rest of us to choose a medical facility, according to new research published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

About 63% of the physicians died in a medical facility, including a hospital, clinic or nursing home. That rate was similar to others in healthcare and people with higher education who weren’t in healthcare. But 72% of people in the general population group died inside a medical facility.

Note: another 2016 study found 27.9% of physicians vs. 32% of the general population chose to die in hospitals, and during the last six months of life physicians were less likely to have surgery (25.1% vs. 27.4%) and less likely to be admitted to the ICU (25.8% vs. 27.6%).

The study didn’t look at the reasons for the small-but-notable preference of physicians to die at home, but they may be symptomatic of the profession. “Doctors see a lot of patients who are treated aggressively at the end of life, and often in ways that seem maybe too intense,” Blecker says. Physicians may also be more familiar with the limitations of care and the quality of life that’s sacrificed with intensive care, he says.

The numbers also reveal that people often end up going against their own wishes at the end. “Generally, there’s an incongruity between what people state as their preferences of how they want to experience end of life and what actually happens,” Blecker says. “Most people say they prefer to die at home, but as we show here, two thirds or three quarters die in some sort of medical facility.”

Palliative care in the U.S. isn’t adequately available yet, and the fact that most Americans want to die at home suggests there’s more work to be done—even among physicians, who still die at medical facilities at high rates. “I think even if the people who should be the best at this are still not dying in the comfort of their home, that we still have a lot more communication and understanding of medical options to get more people to die a ‘good death,'” Blecker says.

Likewise, in 2011, Ken Murray MD (a retired general practitioner), in the viral essay How Doctors Die, highlighted that doctors preferred to die at home with less invasive therapies.

Of course, doctors don’t want to die; they want to live. But they know enough about modern medicine to know its limits. And they know enough about death to know what all people fear most: dying in pain, and dying alone. They’ve talked about this with their families. They want to be sure, when the time comes, that no heroic measures will happen–that they will never experience, during their last moments on earth, someone breaking their ribs in an attempt to resuscitate them with CPR (that’s what happens if CPR is done right).

Almost all medical professionals have seen what we call “futile care” being performed on people. That’s when doctors bring the cutting edge of technology to bear on a grievously ill person near the end of life. The patient will get cut open, perforated with tubes, hooked up to machines, and assaulted with drugs. All of this occurs in the Intensive Care Unit at a cost of tens of thousands of dollars a day. What it buys is misery we would not inflict on a terrorist. I cannot count the number of times fellow physicians have told me, in words that vary only slightly, “Promise me if you find me like this that you’ll kill me.” They mean it. Some medical personnel wear medallions stamped “NO CODE” to tell physicians not to perform CPR on them. I have even seen it as a tattoo.

Note: many patients do not know that the overall survival rate with hospital resuscitation is around 23-25%, making it typically futile (while outside the hospital CPR hovers closer to 10%—although the figures I’ve seen for both of these vary quite a bit within these rangers). Additionally, while no formal data supports it, many colleagues over the years have observed subtle variations in how CPR is performed significantly increase the survival rate, but to the best of my knowledge I have never seen these observations make it into clinical training or guidelines.

To administer medical care that makes people suffer is anguishing. Physicians are trained to gather information without revealing any of their own feelings, but in private, among fellow doctors, they’ll vent. “How can anyone do that to their family members?” they’ll ask. I suspect it’s one reason physicians have higher rates of alcohol abuse and depression than professionals in most other fields. I know it’s one reason I stopped participating in hospital care for the last 10 years of my practice.

To see how patients play a role, imagine a scenario in which someone has lost consciousness and been admitted to an emergency room. As is so often the case, no one has made a plan for this situation, and shocked and scared family members find themselves caught up in a maze of choices. They’re overwhelmed. When doctors ask if they want “everything” done, they answer yes. Then the nightmare begins. Sometimes, a family really means “do everything,” but often they just mean “do everything that’s reasonable.” The problem is that they may not know what’s reasonable, nor, in their confusion and sorrow, will they ask about it or hear what a physician may be telling them. For their part, doctors told to do “everything” will do it, whether it is reasonable or not.

Even when the right preparations have been made, the system can still swallow people up. One of my patients was a man named Jack, a 78-year-old who had been ill for years and undergone about 15 major surgical procedures. He explained to me that he never, under any circumstances, wanted to be placed on life support machines again. One Saturday, however, Jack suffered a massive stroke and got admitted to the emergency room unconscious, without his wife. Doctors did everything possible to resuscitate him and put him on life support in the ICU. This was Jack’s worst nightmare. When I arrived at the hospital and took over Jack’s care, I spoke to his wife and to hospital staff, bringing in my office notes with his care preferences. Then I turned off the life support machines and sat with him. He died two hours later.

Even with all his wishes documented, Jack hadn’t died as he’d hoped. The system had intervened. One of the nurses, I later found out, even reported my unplugging of Jack to the authorities as a possible homicide. Nothing came of it, of course; Jack’s wishes had been spelled out explicitly, and he’d left the paperwork to prove it. But the prospect of a police investigation is terrifying for any physician. I could far more easily have left Jack on life support against his stated wishes, prolonging his life, and his suffering, a few more weeks. I would even have made a little more money, and Medicare would have ended up with an additional $500,000 bill. It’s no wonder many doctors err on the side of overtreatment.

As so much can be said about this immensely complex subject, I will simply share a few of my perspectives:

•I feel very strongly that medicalized deaths should be avoided, that a case can be made hijacking the dying process is one of the most detrimental things medicine has done to humanity, and that in most cases, dying at home is ideal.

•Our society has essentially put doctors into the role priests once occupied, but without the training that role typically requires. As such, doctors are frequently sought out for consultations on life and death despite not being spiritually prepared for that responsibility—which inevitably leads to issues arising.

•In many cases, as I discussed here, hospital care is “futile” because incorrect therapies are being utilized, and modern financial incentives are set so that doctors are not sufficiently trained or supported in bringing sick patients back to health.

Note: a major reason why I am working so hard to build a robust case and interest for forgotten therapies like ultraviolet blood irradiation and why since October, day in and day out I’ve been trying to compile the entire DMSO literature base (which I am now very close to finishing) is because these therapies can radically improve hospital outcomes.

Fortunately, there has been some progress in this area, and the percentage of American deaths in hospitals has gradually decreased while hospice care has become more widely available. Unfortunately, this has dovetailed with medically assisted dying (MAID) being made more and more available (e.g., in 2024, 5.1% of deaths in Canada were from MAID) and gradually being pushed upon patients with chronic physical or psychiatric illnesses socialized medical systems do not wish to address.

Note: one of the most amazing stories I discovered around MAID was certain providers only allowing you to receive MAID if you had been vaccinated for COVID.

Patient Values

Because of the immense power doctors are entrusted with and the ability to harm others (particularly psychologically and spiritually), I believe one of the most critical things in a physician education are medical ethics, but unfortunately, this is also one of the most neglected parts of medical education, resulting in getting a very cursory overview and leading to doctors adopting diametrically opposed positions (with whatever results in a billable medical procedure often ultimately being the “ethical” decision). Likewise, in medical ethics, one of the foundational premises everyone is taught is that patient autonomy and values must be respected—but as things like the COVID vaccine mandates have shown, this also gets discarded when it’s not convenient.

Note: this topic is discussed further here.

In turn, while much could be said about Scott’s process, there were a few points I felt were important to highlight:

First, when Scott realized his condition was terminal, he decided that he wanted to spend his remaining time engaging with his followers through his political podcast as much as possible, even when he was on the verge of death. Had I been in Scott’s position, unless I felt I had critical things I needed to tie up and conclude with this newsletter, the last thing I would be doing with my last days would be being online.

However, those were Scott’s values, so when I saw post where Scott said he expected to pass in the near future, I wanted to honor them and asked a mutual friend to relay this message to him:

Me: Hi Scott, I asked ███ to pass this along to you. When I saw Trump’s 2015 response at the first debate to the Rosie O’Donnell question, I felt there was a real likelihood he’d win, and soon after found your blog. Since then I’ve learned a ton from it and the perspectives I got from you were one of the things that made my newsletter possible. I wanted to thank you for that the numerous times you’ve shared my work on X and I wish you the best of luck with everything.

Scott: Thanks for passing that along. I’m so glad I helped.

Me: Thanks; you helped me a lot and I will do my best to pay it forward.

Note: out of respect for Scott’s autonomy, I deliberately worded my message so that I did not ask for anything or project any emotional needs onto him. This was because a common issue dying individuals and cancer patients run into are others who are not at peace with the situation wanting their anxiety to be addressed (which becomes quite draining once a sizable number of people are doing it). Likewise, because of the deluge of correspondences he was facing, I tried to make it as short and to the point as possible.

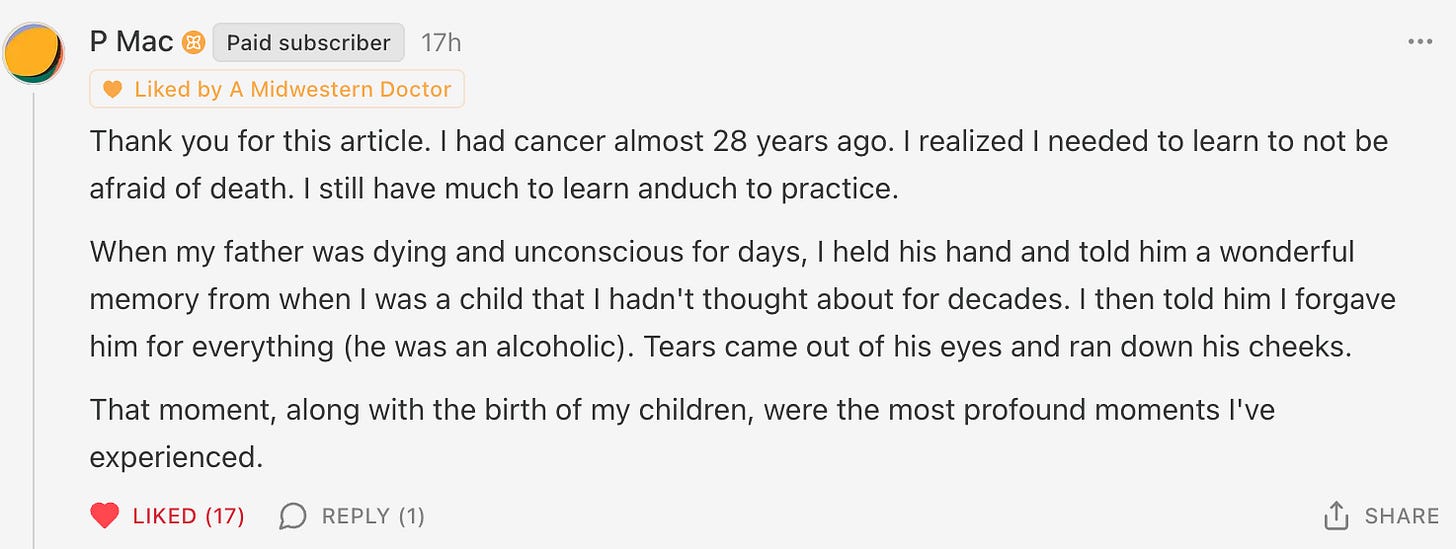

A few hours after receiving that message, Scott then posted this on his page, in turn corroborating that this touched upon the core values he’d adopted at the end of life:

Likewise, once he passed this was posted:

Note: all things considered, I feel Scott handled his dying process quite well (particularly given how much more challenging it is to do when a large number of people are involved in what would otherwise be a very private process) and hence provided numerous useful lessons to us from it.

Society always revolves around competing parties trying to hijack your attention and resources for their wealth and power. Because of this, many people carry belief systems that were implanted within them and cause them to dedicate their lives to pursuing things which do not bring them joy or happiness. In turn, it is frequently only at the end of life (either as they recognizing they are dying or during the moment of death) that these unhealthy filters break, and people realize what actually mattered to them.

Typically, that is some combination of the following:

•Helping and positively impacting the lives of others (e.g., Scott is far from unique in this result).

Note: on the opposite end of the spectrum, individuals who hurt others are often mentally tortured by it, particularly at the moment of death. As such, I ascribe to the viewpoint many spiritual traditions throughout time have adopted—that many of the abhorrent things humans commit (particularly those with power or wealth) would stop occurring if they understood what they were actually doing to themselves each time they perpetuated those misdeeds.

•Being authentic and living true to oneself (rather than suppressing who they were to “succeed” in society and social interactions), expressing what they had wanted to share with others (e.g., “I’m sorry” or “I love you”), and allowing themselves to feel the emotions (e.g., joy or sadness) they bottled up to fit in.

•Being close to family members and friends who genuinely cared about them.

•Taking the time to pursue things with depth they found meaningful rather than being trapped within the inane distractions society fed to them.

•Taking the time to take care of their body and health and pacing themselves at the way they wanted to live rather than overexerting themselves to succeed in the societal rat race.

This hence powerfully reinforces why the medicalization of death is so deeply problematic: the dizzying hospital process often strips away the individual’s autonomy precisely when they most need to retain it. At the same time, the clear-eyed perspectives of those nearing the end of life offer something invaluable to the rest of us, serving as a rare, unfiltered counterweight to society’s relentless pressure to chase superficial pursuits—pursuits that so many later regret having poured their finite time and energy into.

In short, with the dying process, one of the most important things is to recognize exactly what the dying person actually wants and honor it, rather than letting them get swept up by a process where they have no autonomy (and as such, my hope is that this article will give you critical insights for drafting your own living will and advanced care directive so your autonomy is preserved when you are least able to advocate for yourself).

Note: it is also frequently important for associates of the dying person to resolve what they have with them before the individual passes. In the case I shared here it was quite simple (I told Scott what I did because I knew I’d regret it if he passed and I never expressed what I wanted to express to him), but it many cases it can be much more challenging if there are a lot of emotional threads between them. However, regardless of how difficult it is, people normally benefit immensely from some type of resolution prior to death (e.g., the grief from the death will affect them for a much shorter period).

Consciousness and Death

One of the major tensions within our culture has been materialistic science (which effectively became our society’s dominant religion) rejecting the spiritual aspect of our existence and because of this, a wide range of spiritual practices (that have existed far longer than modern science) are routinely disparaged by our society.

Furthermore, while the mechanistic materialistic model can explain many of the phenomena around us, it falls short on aspects of the human experience which are interwoven with spirit. For example, to explain consciousness (and intuition), a belief was adopted that all the neurons in the brain allow it to function as a magical super computer, and because of that, consciousness spontaneously arises along with it subconsciously giving to birth key aspects of the human experience “unscientific” people erroneously attribute to spiritual mechanisms (such as intuition).

For that reason, I’ve tried to touch upon some of the evidence science has collected that undermines its materialistic paradigm, and to lay the foundation for this article, previously discussed two of the great mysteries in medicine.

There I provided the evidence that:

•There are many cases of individuals receiving organ transplants (particularly of the heart) and then adopting the preferences, behaviors, memories and personality traits of the donors. In many cases, these changes are so profound, that it is hard to provide any explanation except that a transference occurred—particularly since in many cases, the individual had no prior way to know those traits came from the donor.

Note: I have also personally seen this happen a few times, and while it’s most common with the heart (where a core component of consciousness is believed by many spiritual traditions to resides), I have also seen other organs create smaller personality transfers.

•When CPR is successful, it creates a modern day miracle that allows those dead to come back to life. Because of this (and other instances where people have come back to life), a large volume of reports have accumulated over the years of individuals with “near death experiences” remembering what happened while they were dead. Furthermore, many of these cases involved their consciousness and awareness existing outside the body (e.g., they can see their body from above or recalled everything that happened in the room while they were supposed to have been brain dead).

Note: beyond the evidence supporting it, I “believe” in this phenomenon because I had a near death experience and some of what I experienced overlapped with the literature in this field. However, I will also acknowledge that many of the people I’ve spoken to who died and were revived had no memory of the in between time.

My reason for highlighting these two points is because they challenge a central dogma of science’s materialistic paradigm—that consciousness resides in the brain and emerges from neural processing. This, in turn, is particularly poignant for the dying process, particularly since many people who bear witness to deaths report a variety of profound occurrences suggesting consciousness transforms and travels at the moment of death rather than it vanishing into thin air once the brain “turns off.”

Note: numerous spiritually attuned doctors and nurses I’ve met over the years shared with me that trait led to them being drawn into hospice care, and that they considered to be the most fulfilling part of their careers, in part because of how much they felt they helped the patients and in part because of the profound experiences they had (some of which were quite astonishing and mirror that described in the literature on “Shared Death Experiences”).

Navigating The Death Process

Due to the fear and rejection our culture places around death, individuals are always seeking ways to address it (e.g., Scott Adams, who had long been agnostic, converted to Christianity shortly before his death). In this article, I’ve hence tried to highlight that:

•How you live your life has a major impact on the quality of the death process, so it is in your best interest to avoid continually putting off living the life you were meant to live.

•There are a variety of spiritual components to the dying experience, and that as one comes closer to the moment of death, they weigh heavier and heavier upon them, and in many cases, they become more and more able to perceive them.

•There are a significant number of things one can do to affect the quality of the dying process.

In the final part of the article I will share what we have come to believe (through working with many patients) are the most important to do during the dying process (from having been with many people at that moment), both from the standpoint of the dying individual and for someone seeking to support them, along with our spiritual perspectives of what is actually unfolding and how it weaves together with conventional medical approaches.