The Great Dangers of Blood Pressure Medications

Unraveling the blood pressure scam

Story at a Glance:

High blood pressure (hypertension) is increasingly common, with more people diagnosed each decade.

This is because the threshold for “high” blood pressure keeps getting lowered—despite no evidence existing that those levels reduce deaths.

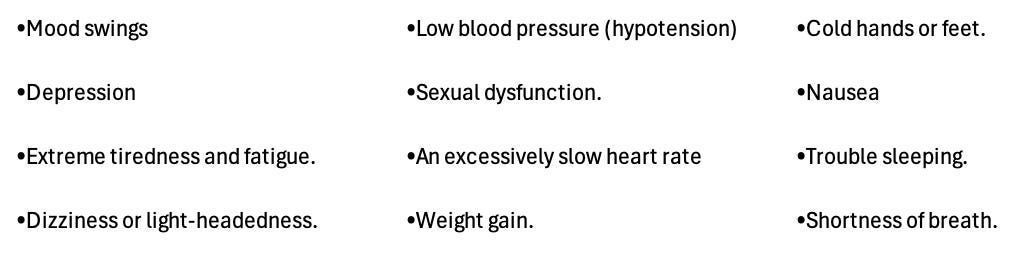

Excessively low blood pressure carries significant risk. Likewise, many of the blood pressure medications have common and significant side effects doctors often don’t recognize.

In this article we will review the key aspects of each common blood pressure lowering medication and healthier ways to address elevated blood pressures.

Frequently, when you dig into medical myths, you discover that many of the dogmas that underlie a popular drug are actually sales slogans a marketing company created. For instance, cholesterol lowering statins are widely prescribed despite the fact lowering cholesterol does not prevent heart disease (in fact cholesterol protects you, so when it’s low, you more likely to die), statins don’t prevent death, and these drugs harm 20% of users (often severely).

In turn, since so many people have been severely harmed by The Great Statin Scam, more and more public figures, such as comedian Jimmy Dore and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. have begun to speak out against this:

Sadly, statins are not the only mass-prescribed drug that’s marketed on deceptive premises and frequently makes the problem it “treats” worse. For example:

•A chemical imbalance from low serotonin was never linked to depression (in fact patients who commit suicide are found to have elevated brain serotonin).

•Acid reflux is due to too little acid in the stomach (as acidity gives the stomach’s opening the signal to close). However, in medical school, we are always taught it is due to too much acidity.

•"Sleeping" pills are actually sedatives that block the restorative phase of the sleep cycle.

Each of these drugs in turn is immensely harmful to their users, but due to how effectively their myths were established (just like “safe and effective”) they continue to be used by large numbers of people and harm them.

In turn, when you look into blood pressure, a similar pattern emerges. As I showed in the first part of this series there are two huge issues with this:

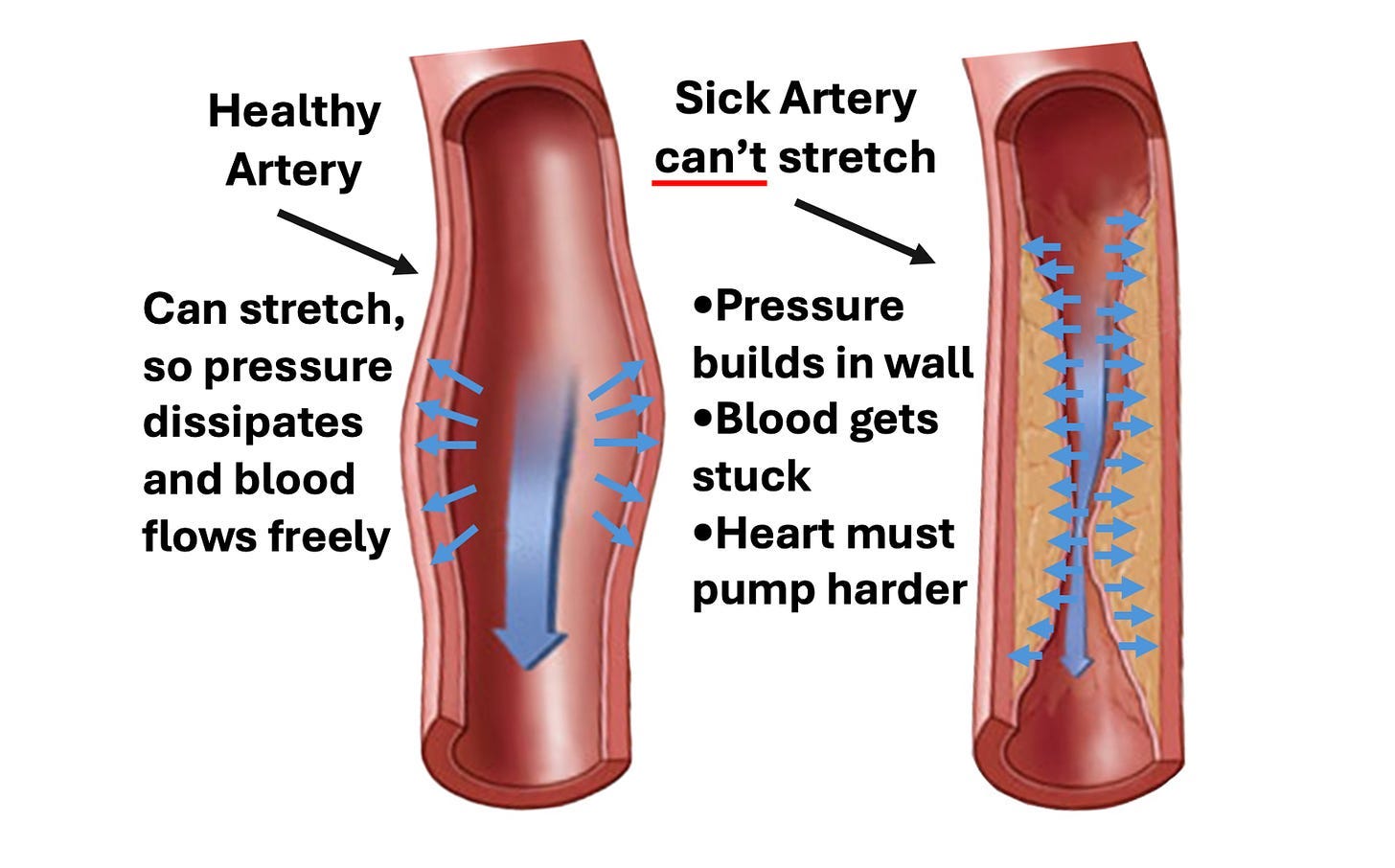

We have it backward. High blood pressure is a symptom not a cause of arterial damage.

There's no evidence that aggressively lowering blood pressure saves lives:

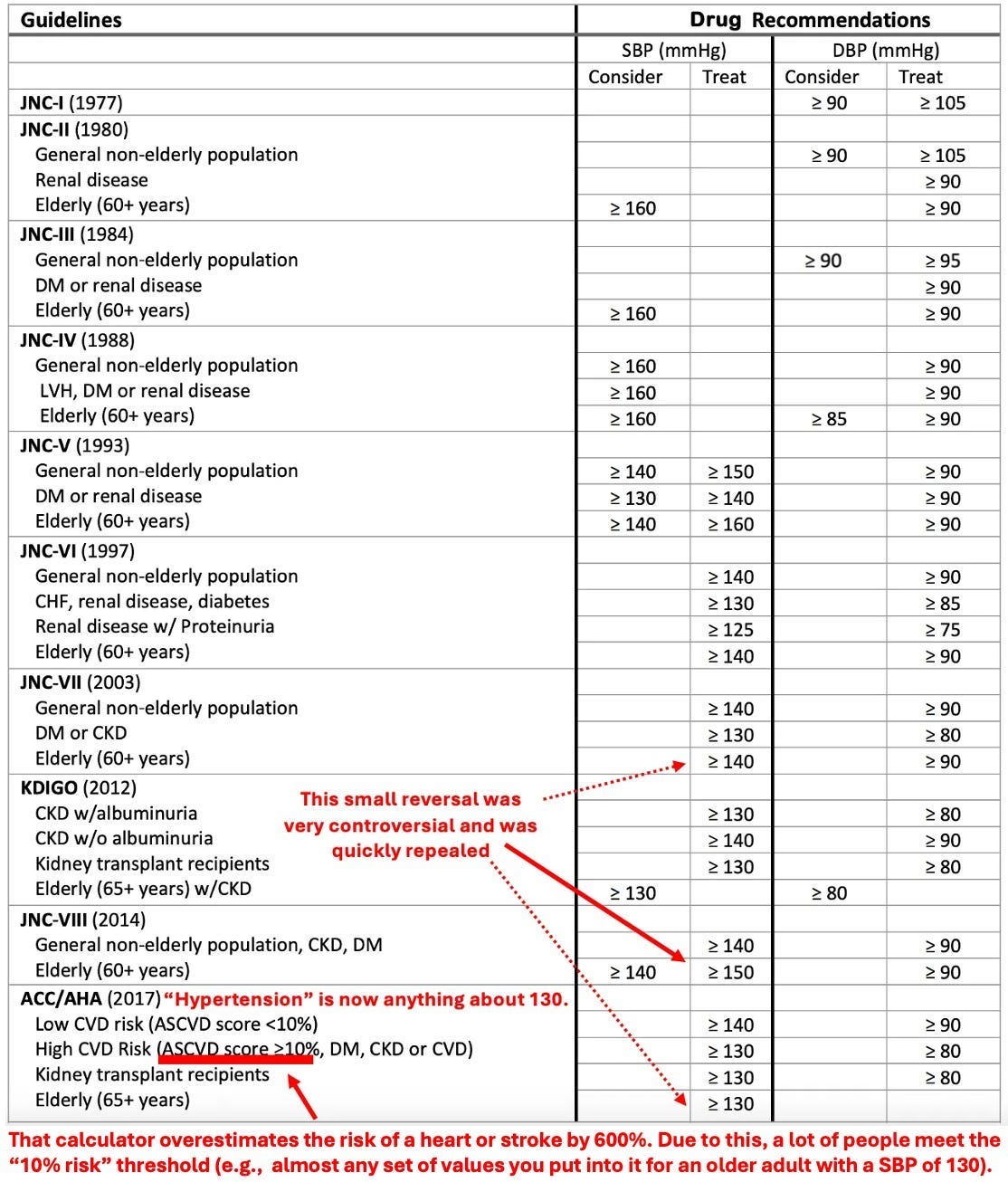

Changing Guidelines

When the blood pressure craze took off, there was a rush to bring the blood pressure lowering drugs to market before their benefit was actually proven (outside of a few short term studies which showed a small benefit for people with very high blood pressures).

That mindset in turn cemented itself, so as the years have gone by, without evidence to support it (and contrary data being ignored), the blood pressure thresholds keep on getting lowered and more and more people are being put on blood pressure lowering medications. Because of this, roughly 60 million American adults (23%) take these drugs.

However, excessively lowering blood pressure cuts blood flow to parts of the body that can’t function without sufficient blood flow. For example, blood pressure medications increase the risk of kidney disease,1,2 and suddenly passing out (from insufficient blood flow to the brain) is one of the most common side effects of blood pressure medications.

My best guess is that this inexorable march to putting everyone on these drugs is due to some combination of the following:

•Research funding is available for these areas (e.g., from the drug manufacturers) hence being a safe area of research for academics to explore.

• It illustrates the “if you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail” phenomenon and the medical profession's desire to find more justifications for using its tools (especially since humans tend to double down on their existing approach when it fails rather than consider a new one).

•"Experts" on guideline panels are paid to create recommendations that result in more and more people taking the drugs, a sadly common phenomenon in medicine (e.g., in this article I conclusively showed how that happened with statins).

Let’s now look at how the blood pressure guidelines have changed over the years.

Note: as these guidelines show, originally the focus was on treating diastolic blood pressure under the belief the heart had to “work harder” if there was too much blood in the circulation. I believe this is helpful to note since it was believed for decades (but now is not) and hence illustrates how arbitrary many medical dogmas are.

To quote the 2017 guidelines:

“Rather than 1 in 3 U.S. adults having high blood pressure (32 percent) with the previous definition, the new guidelines will result in nearly half of the U.S. adult population (46 percent) having high blood pressure, or hypertension.”

Note: this rate further increases with age (e.g., 79% of men and 85% of women over 75 now have hypertension, while 71% of men and 78% of women now meet the threshold to start blood pressure medications).

The Effects of Hypertensive Medications

In many cases, the actual mechanism of a drug greatly differs from the purported one (e.g., the tiny benefit statins provide is most likely due to them reducing inflammation).

In the case of blood pressure medications (which each work in a different manner), very different degrees of benefits are seen from their use despite them creating the same drop in blood pressure. This in turn strongly argues that their benefits are not due to them lowering blood pressure, but rather how each one specifically affects the body. To illustrate:

•A 1997 paper in JAMA reviewed the literature and found significantly different benefits from the antihypertensive drugs depending on which type was used.

•A 1998 review found that the (known) cardiovascular benefits of ACE inhibitors were not seen with calcium channel blockers, despite the latter having a more significant effect on blood pressure.

•A 2000 study of 3577 diabetics found that a specific ACE inhibitor, despite minimally reducing blood pressure (a 2.4 reduction in SBP and 1.0 reduction in DBP) had a massive effect (a 25% reduction) on the risk of a heart attack, stroke or cardiovascular death.

•A 2007, eight year long (and NIH funded) double-blind study of 42,418 subjects found that when two different types of blood pressure medications were used, there was no difference in their effect on blood pressure but simultaneously, found their rate of preventing heart failure varied by 18% to 80% depending on the drug, leading the investigations to conclude: “blood pressure reduction is an inadequate surrogate marker for health benefits in hypertension.”

Harms of Hypertensive Medications

The typical management of blood pressure is to use a combination of drugs until they collectively achieve the desired blood pressure and simultaneously to switch out drugs that cause too many side effects for ones the patients can tolerate.

This is a problem, because, as the previous section showed, the drugs have very different effects on the body and should each be considered on the basis of whether their individual effects are appropriate for the individual patient’s situation rather than whatever reaches the desired blood pressure—but as that would get in the way of drug sales, it never happens.

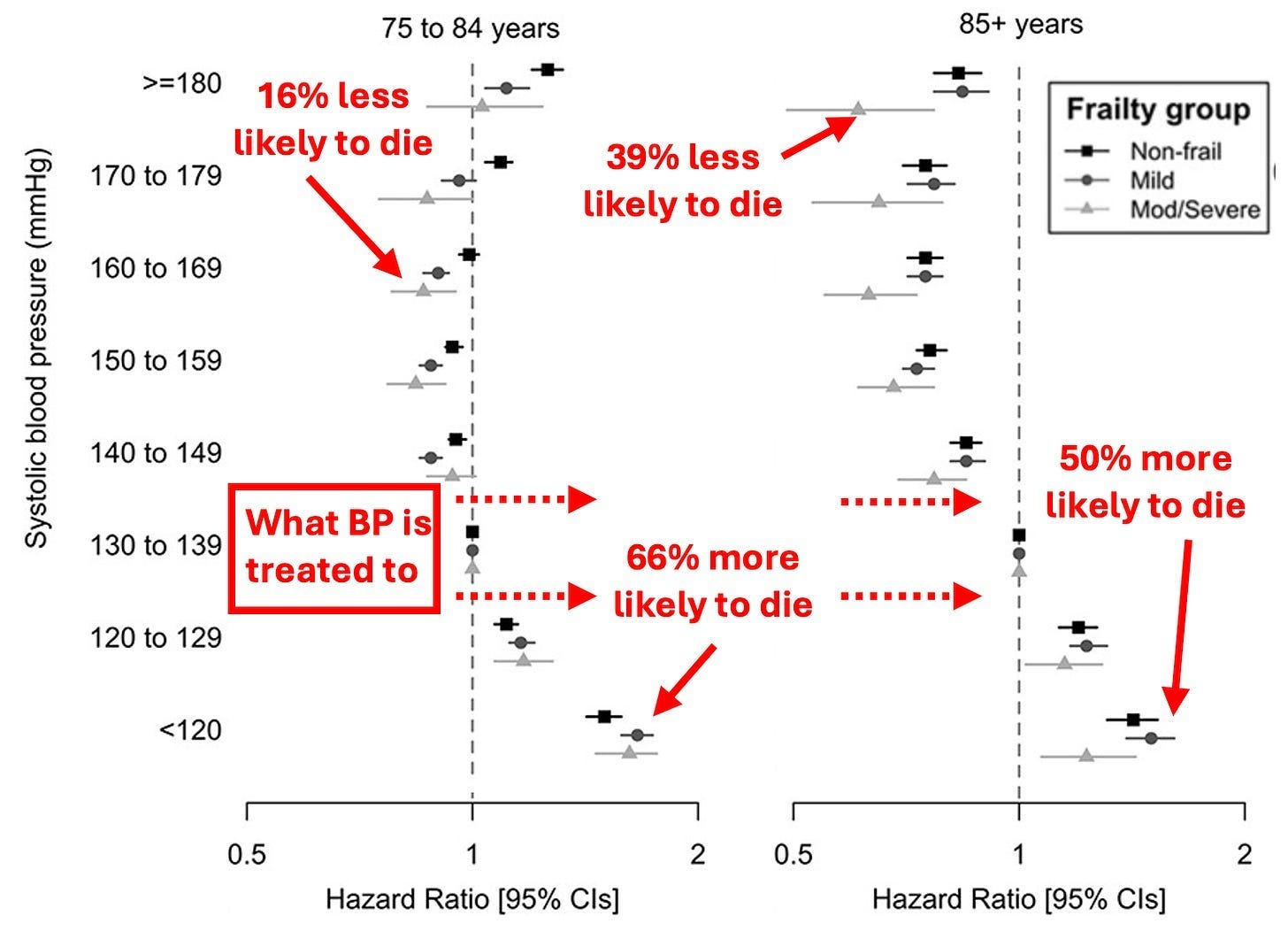

Typically, the most common side effect of blood pressure medications are complications of poor perfusion. For example, blood pressure medications increase the risk of fainting by 28% and are notorious for causing older individuals (who have calcified arteries and hence difficulty getting blood to the brain without insufficient blood pressure) to become lightheaded and then suffer falls that can be devastating.

To illustrate, a 2014 JAMA study of 4961 adults over 70 with hypertension compared 14.1% who received no antihypertensive medications, 54.6% who were on moderate-intensity medical therapy, and 31.3% on high-intensity medical therapy. They were monitored for three years, during which 9% experienced falls, and 16.9% died.

Note: in 2007, an important Israeli study was conducted that found that discontinuing an average of 2.8 drugs per elderly patient reduced their 1-year death rate from 45% to 21% and hospitalization rate from 30% to 11.8%.

Emergency medicine also recognizes the risks of aggressively treating high blood pressure, as rapid reductions can impair blood flow to the brain, potentially triggering ischemic strokes. Similarly, organs like the brain and kidneys suffer when blood pressure is too low. Hypertension drugs increase the risk of an acute renal injury by 18%, and in patients who have end stage renal disease low blood pressure increases mortality by nearly 39%.

Many other more serious diseases also result from low blood pressure, especially in the organs most sensitive to a loss of blood flow. For example, low blood pressure is strongly linked to cognitive decline (since the brain needs adequate blood to function). Likewise, as you lower the blood pressure the kidneys start to struggle as they require sufficient blood flow to function.

For example, when adults 75 and older with blood pressures below 130 were compared to those with ones between 130-140, those with lower blood pressure were 11-62% more likely to die.

Additionally, each blood pressure medication works differently. On one hand, this is a good thing because it allows each of them to exert unique therapeutic benefits independent of their effect on blood pressure, but on the other hand, it means they each have unique side effects.

Presently, four main types of antihypertensive drugs exist:

1: Diuretics (the oldest): These drugs lower blood pressure by increasing urination by blocking the reabsorption of sodium in the kidneys. Many different types of diuretics exist with slightly different side effect profiles and different electrolytes they affect, but generally, these drugs:

•Cause a wide range of symptoms from electrolyte imbalances, particularly of sodium and potassium (e.g., low sodium levels are a common cause of weakness and hospital admissions, while low potassium affects 8.2% of users—occurring at a rate 973% greater than those not on the drugs).

•Cause many of the gastrointestinal side effects associated with dehydration (due to the drugs effectively dehydrating you).

•They (depending on the class) can sometimes create sulfa sensitivities or allergies.

•They cause many of the general effects associated with low blood pressure (e.g., lightheadedness).

•Some of them (ie. the thiazides) also increase uric acid levels, which may explain why these drugs increase the risk of diabetes or why they significantly increase one’s risk of gout.

2: Beta-blockers: These drugs slow the heart and make it pump less forcefully. This is found to be very helpful for heart failure patients, but simultaneously has a variety of common side effects such as constricting the peripheral arteries. Typically, patients have the greatest difficulty tolerating beta blockers and frequently report a worsened quality of life from them (which doctors sadly often don’t recognize). Some of their most common side effects include:

3: Calcium channel blockers: These reduce the force of contraction of the heart, dilate arteries by relaxing the smooth muscle in them, and somewhat slow the heart rate. The major issues with these drugs are that they cause edema (swelling) throughout the body (affecting between 5.7-16.1% of users depending on if a low or high dose is taken) and frequently cause dizziness, lightheadedness, or constipation. These drugs are often quite helpful for resetting an abnormal heart rhythm, but also can cause other symptoms such as tiredness, headaches, abnormal heart rates, and shortness of breath.

4: ACE inhibitors (and related medications): When the kidney does not have enough blood, it releases a hormone that sets off a cascade within the body to raise blood pressure. ACE inhibitors in turn block that cascade and most doctors in practice consider the ACE inhibitors to be the most beneficial to the body (e.g., they are commonly prescribed for diabetes and heart failure).

The most common side effect associated with these drugs is a chronic dry cough (which patients often develop over time as they become sensitized to the drugs—with estimates of its frequency ranging from 3.9% to 35% of users—e.g., this detailed review determined it was 8.0%). Other common side effects include headaches, lightheadedness, and a loss of taste (although may other side effects have also been linked to these drugs). More severe side effects include a 26% increased risk of acute kidney injuries (affecting 1.5% of users), a 103% increased risk of hyperkalemia (which can be quite dangerous and affects 4.8% of users), and a 19% increase in the risk of lung cancer.

Under Recognition of Side Effects

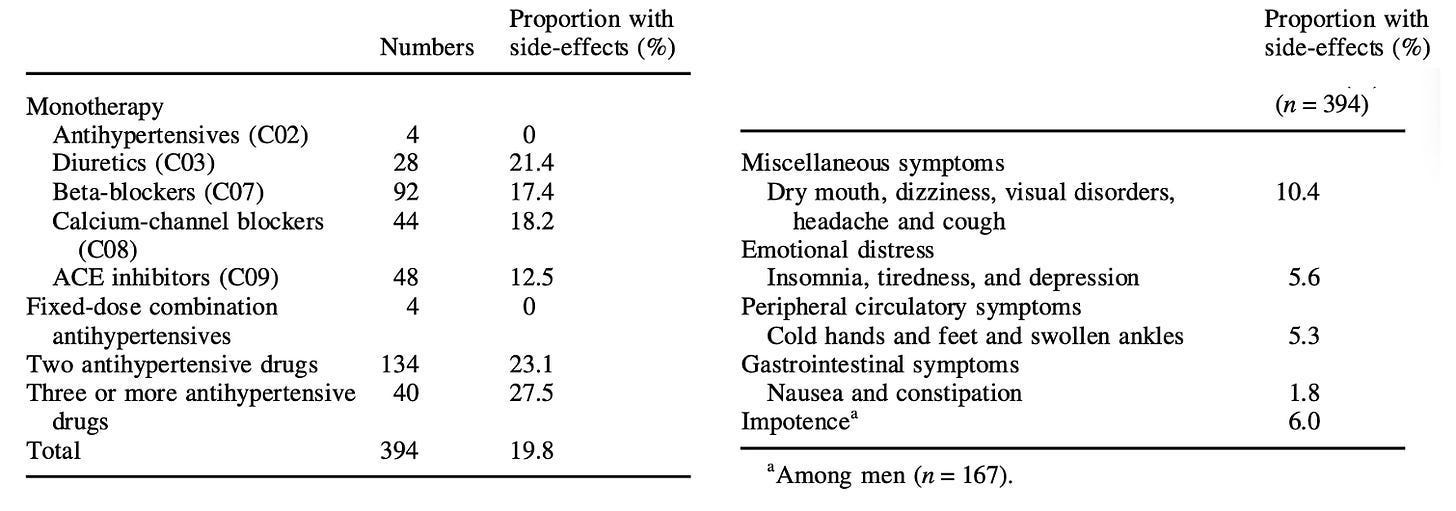

While the numbers I just showed are quite concerning, I believe they actually underestimate the rate of side effects as much of that data comes from industry clinical trials which deliberately finds ways to downplay their drug’s side effects. Because of this, I believe patient survey’s provide a far better perspective on the rate of symptomatic side effects. Consider for example this 1995 Survey in Sweden which found roughly 1 in 5 users experience side effects:

Because of these side effects, patients frequently stop taking antihypertensives.

For example, a study of 370,000 patients under 65 between 2007-2014 found 23.5% stopped taking the drugs within 270 days of starting them, while 40.2% of those who continued often skipped the medications.

Given such a high discontinuation rate of these drugs, one of the most surprising things about blood pressure drugs is how little awareness exists regarding their side effects, especially amongst doctors (e.g., the article I just cited acknowledged side effects were a reason for discontinuation but insisted it was due to patient ignorance about the importance of the drugs). All of that was best shown by this 1982 study (which would not be repeated in today’s political climate) that compared how patients, their families and their doctors felt about the effects of these drugs on them. It found:

Salt

Finally, aggressive salt lowering is frequently advised to patients. I personally do not support this approach since:

•As mentioned before, significant salt reduction has almost no effect on blood pressure. Furthermore, something many people don’t consider is that patients in the hospital are routinely given large amounts of IV sodium chloride, in many cases receiving ten times the daily recommended sodium chloride we are supposed to consume. Despite this, their blood pressure does not rise.

•Low sodium levels are strongly correlated with a risk of dying (e.g., the salt consumption target we are recommended to follow increases one's risk of dying by 25%). Likewise, a common reason for hospital admissions is symptoms resulting from low sodium levels (as once they get too low, they can be very dangerous), and 15-20% of hospitalized patients have low sodium levels at admission.

Note: I presently believe many of the associations between salt and heart conditions are due to the zeta potential destroying aluminum processed salt often contains as a desiccant—something not for example found in natural salt products or IV saline given at hospitals. Conversely, I believe many of the benefits from hospital care are a result of IV fluids being routinely given as they partially restore the physiologic zeta potential.

Conclusion

One of the biggest problems with medicine is that it’s been transformed from an artful doctor patient relationship to a disconnected interaction where the doctor carries out clinical algorithms. As I’ve tried to show in this article, the current guidelines we use to treat everyone’s blood pressure to are flawed, and need to replaced with approaches individualized to each patient’s circumstances (e.g., a chronically stressed adult in their 20s with a blood pressure consistently above 160 needs to address their blood pressure, whereas a 160 blood pressure in an older adult is often not an issue).

Likewise, the ways we lower blood pressure are far too standardized to meet the needs of each individual patient. Treating the natural causes of high blood pressure (e.g., chronic anxiety, a sedentary lifestyle, blood stagnation coming from an impaired physiologic zeta potential, or missing micronutrients) should come before medications. Similarly, if used, the blood pressure medication used should be selected on the basis of it best fitting the individual patient’s situation at the lowest dose that works rather than numerous medications being indiscriminately piled onto the patient until their target blood pressure is reached.

While vast societal forces are pushing us to a depersonalized model of algorithmic medicine that cannot create health, the widespread lost of trust in our medical authorities (due to the COVID-19 response) is now creating a push in the opposite direction. In turn, it is my hope and belief that many things the medical orthodoxy has habituated us to like needing an ever lower blood pressure can now be critically re-examined and that we are now in an era where it may be possible to make America healthy again.

Author’s note: This is an abridged version of a longer article about the great blood pressure scam which goes into greater detail on the points mentioned here, the dangers of blood pressure medications and natural ways to safely lower blood pressure.. That article and its additional references can be read here.

To learn how other readers have benefitted from this publication and the community it has created, their feedback can be viewed here. Additionally, an index of all the articles published in the Forgotten Side of Medicine can be viewed here.

In 2015, I was prescribed Terazosin. The VA doctor (my PCP) had asked if I had difficulty urinating due to BPE. I told him I generally got up in the night one time. He mentioned Terazosin, and I asked what the potential side-effects were. He answered, "There are none." When I replied that all medications have side-effects, he told me, "You are starting on a 1/20th dose - 1 mg - some men take as much as 20 mg. At that time I was ignorant regarding the nefariousness of comparing one patient to another (with, obviously, quite different symptoms, conditions, and needs). I started the drug, which caused my blood pressure (normal) to fall. I experienced Transient Global

Amnesia events (I was still working in I.T.) to great embarrassment. But, my judgment was impacted, as well as memory, and I kept taking my pills; it's unexplainable to someone who isn't impacted by a drug, and what it does to judgment and daily living. Ultimately, I blacked out (an FDA-recognized side-effect - "sudden fainting") at the wheel on the interstate. According to a witness, I drifted off the right side, went through a field at an estimated 70 mph, and smashed head-on into an oak tree. I woke up in the hospital with a broken back, sternum, ribs, arm, wrist, and was concussed and had been in a coma. I was told I wasn't expected to live when brought in. Later, a doctor told me I'd likely never walk again. I said, "Watch me." He didn't like that - his eyebrows shot up, he stared a moment, then walked out of the room with the back of his head going back and forth. (He likely thought I'd fallen asleep at the wheel). It took me months to piece together what had happened to me: meantime, my original doctor tried to reverse my medical timeline to make it appear that he'd prescribed the med after the accident. I'll never trust another doctor: Always seek second and third opinions, and follow your "sixth sense" - it will alert you. Mine nearly did, but I made a mistake the day I accepted that drug. I will be detailing my experiences/recovery at my political site, ScottSense in the coming months (plainsenseandsanity.substack.com). Please watch for it. Meantime, you can see the latest column, "Why DEI = DIE."

I'll graduate this year as a doctor and I find this article extremely important. I always felt like there is something wrong with prescribing drugs away like they're candy, and not fully acknowledging the side effects. I hope to be able to learn more and personalize my treatment models for all patients.