How Big Pharma Sold Depression and Its Treatment to the World

Why antidepressants fail many patients and a review of the forgotten cures for depression

Story at a Glance:

•After the SSRIs were developed, their manufacturers realized the population needed to be convinced they were suffering from depression so as many people as possible would buy their drugs.

•The tricks the drug industry used to perform this were remarkable and have many parallels to how the predatory pharmaceutical industry pushes many other drugs on us.

•While a minority of patients (about a third) benefit from antidepressant therapy, the majority do not (termed “treatment resistant depression”), but unfortunately, until recently there have been minimal options available for these patients.

•Much of this results from depression being viewed as a single illness, rather than a myriad of conditions with somewhat overlapping symptoms.

•In this article I will discuss the most effective non-pharmaceutical approaches I and my colleagues have come across for treating depression.

When you read history textbooks, you will frequently notice events of the past (and the society going along with them) being cast in a negative light. Yet in many cases, when the exact same processes occurs in the modern era, it is not cast in the same negative light—even when many prominent dissidents are actively explaining why what we are doing is completely insane.

In turn, the hope I and many others share is that in the not-too-distant future, the way our society handled COVID-19 (e.g., locking down the country, suppressing off-patent treatments, mandating a clearly flawed vaccine and aggressively censoring anyone who spoke out against this) will be acknowledged as a profound mistake by the history books. Remarkably, despite the propaganda apparatus doing everything it could to prop the COVID vaccine up, both due to its immense danger and a dedicated group of online activists who exposed that danger, public opinion has soured on the vaccines and we are now beginning to see official proceedings looking into them.

Likewise, the hope I and many others hold is that the public becoming aware of the immense dangers of the COVID-19 vaccines will make them open to recognizing how many other unsafe and ineffective pharmaceuticals have been pushed onto the market despite an overwhelming degree of evidence arguing against their safety and efficacy.

In my eyes, one of the worst offenders are the SSRI (and SNRI) antidepressants, drugs which have many parallels to illicit stimulants (e.g., cocaine) and which I suspect in the future will be viewed by the history textbooks the same way they now look at how dangerous drugs like heroin, cocaine, opium and methamphetamine were freely available in pharmacies of the past.

In a recent series, I presented the wealth of evidence that the SSRIs:

•Sometimes cause psychotic behavior which frequently results in suicide and sometimes in mass-murder (e.g., school shootings).

•Cause abnormal thoughts and often make one feel as though they’ve “lost their mind.”

•Cause aggressive behavior, agitation, insomnia, anxiety or restlessness and Bipolar disorder.

•Cause sexual dysfunction and numbs one to the experience of life (e.g., it takes away what gives you joy and the emotional reactions to a dangerous situation).

•Cause birth defects.

•Are extremely addictive (the process one must go through to withdraw from them is extremely unfair.

Note: according to John Virapen, a (no longer available) German study found approximately a third of babies born to a mother taking SSRIs display withdrawal symptoms at birth, with 16% displaying severe withdrawal symptoms).

The above symptoms are frighteningly common (e.g., sexual dysfunction affects approximately half of SSRI users), and in addition to these, a variety of other concerning (but less common) side effects also occur.

However, despite the litany of evidence arguing against the wisdom of mass prescribing these drugs, a deluge of complaints to the FDA (and public hearings) about the SSRIs, and numerous successful lawsuits filed against the manufacturers, nothing has been done about it. Rather, the FDA has done everything it could to fight for the industry and suppress the evidence of SSRI harm from seeing the light of day.

In a recent article, I attempted to detail exactly how this transpired as I felt the corruption and malfeasance demonstrated throughout the process provided a poignant case study to explain the FDA’s otherwise inexplicable behavior we’ve all seen throughout the pandemic. Furthermore, I believe these acts are representative of a broader trend—the march towards economic feudalism we have seen enacted over the last 50 years, where unaccountable corporations are enshrined as the fourth branch of government and the majority of the (increasingly impoverished) population are forced into economic servitude under these corporations. I believe like the feudal system of past, this system exists both to maximize the wealth of the upper class and to have an easy way to implement compliance throughout the entire population (e.g., by forcing people to get a vaccine they knew was extremely dangerous as otherwise they would be out of work).

Note: the relentless march to economic feudalism (e.g., how the lockdowns were a devastating assault on the working class) is discussed in further detail here. I am of the belief that maintaining a perpetual state of physical and mental illness is one tool the upper class uses to control the populace (as being sick takes away your ability to act independently while simultaneously making you dependent on the system for medical care).

In turn, one of the most concerning aspects of the lockdowns was the huge spike in mental health issues they created, and likewise psychiatric effects are a common side effect of the vaccines (e.g., an Israeli study found that about 26.4% of individuals with pre-existing anxiety or depression reported an exacerbation from the booster). Unfortunately, while the psychiatric complications of the lockdowns are at last being discussed, the main solution being proposed to treat them is “more psychiatric care” (which means more drugs).

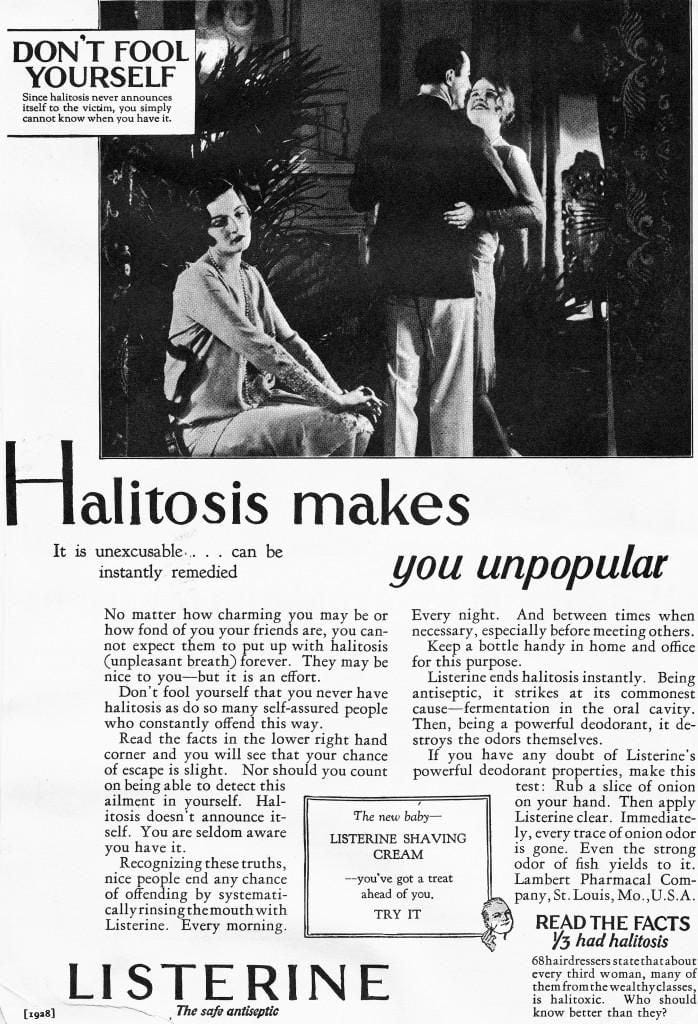

Halitosis

After Listerine was created in 1880, a variety of uses were proposed for it (e.g., as a surgical antiseptic or mouthwash) and the product had modest sales. Searching for a way to increase them, its marketing team eventually had an epiphany. Taking the latin word for breath (halitus), they added on “osis” to make it sound pathological and created a new disease that Listerine just so happened to “cure.”

Following this, an immense marketing campaign was made to familiarize the population with halitosis (bad breath) and to make them as fearful about it as possible.

Who could forget Edna? The quintessential damsel with every trait that society admired—save for her unwitting battle with halitosis. Listerine’s gripping ad campaigns chronicled Edna’s heart-wrenching saga, emphasizing the social implications of bad breath [such as no one wanting to marry you].

Note: at this time, many companies were profiting off of selling the emerging middle class ways to cater to their social anxieties.

This campaign, in turn, was remarkably successful, earning it a permanent place in the history books:

Listerine skyrocketed from modest annual sales of about $100,000 in 1921 to a whopping $4 million by 1927. To provide context, in today’s currency, that’s an astounding rise from $1.3 million to $57.5 million. By the late 1920s, Listerine stood tall as America’s third-highest print advertiser.

What’s particularly interesting about the halitosis saga is that while it is widely disparaged since it revolved around the creation of a largely fictious disease and preying on the insecurities of the public, it is simultaneously widely praised for its effectiveness.

In turn, countless groups have copied Listerine’s tactic of using fear to sell an unneeded product, but as time has moved forward, fewer and fewer people called out those fear based campaigns.

Recognizing how problematic it is when pharmaceutical companies had a blank check to push their products on the public, governments around the world wisely made advertising pharmaceutical directly to consumers illegal. Unfortunately this was the case until 1997, at which point Clinton “legalized” direct pharmaceutical advertising to consumers.

Since the primary expenditure in the pharmaceutical industry is not drug development or production, but rather advertising, this change opened the flood gates to them buying out the America media (which is essentially why the mass media stopped discussing any dangerous drug on the market).

Note: this news article discusses Kim’s work to stop direct to consumer pharmaceutical advertising.

Disease Branding

Within the pharmaceutical industry, the process of creating a new disease or increasing the public’s awareness of an existing condition is known as “disease branding,” and is one of the most common steps taken when attempting to sell a pharmaceutical. While sometimes subtle, in many cases, these campaigns are blatant enough that many can spot them (e.g., consider how much fear the media stirred up about COVID in 2020 while simultaneously constantly telling us that a miraculous vaccine which could end all of that was right around the corner).

Note: presently, many believe one of the most egregious examples of the medical industry creating a new disease to push its products is the sudden widespread emergence of “gender dysphoria.”

Mental health is a particularly unfortunate area for disease branding to enter into as virtually anything can be turned into a disease and sold with the same marketing tactics pioneered for Listerine:

Patty Duke provided the 2008 American Psychiatric Association meeting with its celebrity patient story. AstraZeneca sponsored her talk, and the company spokesman who introduced her.

The Oscar-winning actress, clad in a pumpkin orange dress, told of how she had suffered from undiagnosed bipolar illness for twenty years, during which time she drank excessively and was sexually promiscuous. Diagnosis and medication “made me marriage material,” she said, and whenever she speaks to patient groups around the country, she hammers this point home. “I tell them, ‘Take your medicines!’” she said. The drugs fix the disease “with very little downside!”“We are beyond blessed to have people like you who have chosen to take care of us and to lead us to a balanced life…. I get my information from you and NAMI [National Alliance on Mental Illness], and if I resisted such information, I would deserve to have a net thrown over me. When I hear someone say, at one of my talks, ‘I don’t need the medication, I don’t take it,’ I tell them to ‘sit down, you are making a fool of yourself.’”

Note: while this presentation was met with thunderous applause by the attending psychiatrists, many safety issues exist with “Patty’s” medications, and I frequently observe them triggering personality changes which make it quite challenging for the individuals to have intimate relationships.

One of the most poignant examples of how depression was branded to the world comes from Japan, and is discussed within the documentary “Does Your Soul Have a Cold.”

By following the lives of five Japanese individuals this documentary explores the problem of depression in Japan and how the marketing of anti-depressant drugs has changed the way the Japanese view depression.

Marketing of anti-depressants did not begin in Japan until the late 1990s and prior to this, depression was not widely recognized as a problem by the Japanese public. Since then, use of anti-depressants has sky-rocketed and use of the Japanese word "utsu" to describe depression has become commonplace, having previously been used only by psychiatric professionals.

This new awareness was greatly influenced by Western pharmaceutical companies’ advertising or “educational campaigns,” which included the slogan “Does Your Soul have A Cold?” The film is an intimate and purposely unresolved look at five young people taking antidepressants in Tokyo. It is a meditation on the issues of globalism, pharmacology, and social shame towards mental illness, as seen through the everyday lives of these people. The film does not feature any “specialists” of “experts” and instead foregrounds the experiences of the people who are suffering from depression and trying to find a way out.

Creating Depression

When Prozac was first created, Eli Lilly actually had no intention of using it to treat depression. Rather to quote John Virapen, the executive who was responsible for getting it on the market:

For some time, they had been doing research for an antidepressant, which influenced serotonin levels. Starting in the 1960s, research had been carried out on these substances, to find out what role they had played in sensory perception or in emotional perception. One consideration was to suppose there was a certain balance of serotonin levels, which was good. Imbalance on the other hand would lead to depression, to hyperactivity and much more.

Fluoxetine [Prozac] was a new active ingredient from Eli Lilly’s laboratory…which turns the regulating switch of the serotonin balance and supposedly restores the balanced, ideal state. But we were in the 1980s and at that time, only those receiving clinical treatment [e.g., those in mental hospitals] took psychotropic drugs. Nevertheless, while studying fluoxetine, an interesting side effect occurred, which the company bosses deemed to be much more lucrative. Some of the test subjects had lost weight, while taking the new active ingredient.

If being overweight had only been a problem for a small amount of people, it wouldn’t have interested the medical industry. Their increasing number makes overweight people interesting. Furthermore, overweight people are in more developed and rich countries. In terms of marketing, that is good.

What is even bigger than the number of people people is the number of people, who think they are fat, just like the number of those who can be talked into being fat.

This group became, and still is become part of their clientele by means of teaching. Teaching aids: the ideal of beauty, which is shaped by the so-called ultra-thin models and actresses.

Put both of those groups together — now that is a market. Sick people and those who are talked into being sick — that’s what the blockbuster needs.

In short: fat people are a very good sales market. The only snag is to get the active ingredient approved as a weight-reducing drug, since further extensive studies and tests would be necessary. But Eli Lilly was in a hurry. Every day without the wonder drug on the market was costing them money. So they decided to aim for approval of the active ingredient, Fluoxetine, as an antidepressant. Then, once it had been approved, it is easier to extend the approval to other therapeutic indications. That’s normal and a valuable trick of the pharmaceutical industry, which you can see over and over again. Once the regulatory authority has said, “yes” it is more difficult to justify a “no” the second time.

Unfortunately, the data on Prozac was abysmal (it failed to benefit patients and frequently harmed them), to the point most psychiatrists Virapen consulted burst into laughter at the thought he was seeking an approval. Knowing his career depended on it, Virapen eventually located a key “independent” expert responsible for Prozac’s approval in Sweden who happily accepted a (now proven) bribe.

After receiving tentative approval for Prozac, Virapen was contacted by Sweden’s health authority to begin negotiating the price for their drug. Being an excellent salesman, he was able to negotiate a much higher target price for Prozac than either Lilly or Virapen expected to earn, 1.20 per dose of a 20 mg Tablet (approximately 3.36 in today’s dollars). What followed provides a remarkable window into how the current status quo came to be.

Note: my time in medicine has more and more led me to conclude that business considerations rather than scientific ones frequently determine what the eventual standard care of is.

The price I’d negotiated for an incompletely tested, faulty product, which droves and still drives a lot of people crazy or to their death, was the basis for gaining approval, throughout the world. The connection between dose and price is still the basis for medical recommendations, around the world. You cannot take less than that dose; you always take more than that amount.

The director of [Sweden’s] medical review board is recognized worldwide as an expert, had reported from her own clinical studies, that, with as little as a quarter of the dose, i.e., 5 mg, there had been difficulties and patients had tried to commit suicide…it was this highly respectable figure who then managed to prevent the approval of Prozac in Sweden. She simply refused to approve a 20 mg dose, if a 5 mg dose wouldn’t be offered at the same time, as well. Eli Lilly didn’t like that. The price for a 20 mg dose had been determined. A 5 mg dose would have meant a loss in turnover of 75 percent. Lilly was very sensitive to that since this loss in value would have consequences for other countries, where they were still negotiating. For instance, Lilly could say in a short timeframe in negotiations in the other countries: “You want to nail us down to one dollar? In Sweden, the price is $1.20…”

Note: a key reason why the SSRIs are so addictive (as discussed in this recent article) is because their dose is far higher than what patients need, hence making them very challenging to safely withdraw from.

In the end, the active ingredient didn’t get approval in Sweden. Which probably shows clearly that, at no time whatsoever, was Eli Lilly interested in the well-being of their patients but was only out for Profit.

And in that regard, it had been worth it. Fluoxetine became a large commercial success — especially in the United States and Great Britain — like there had never been before in the history of the pharmaceutical industry with its 20mg dose and “my” price. Marketing made it a fashionable drug. Then, there weren’t many depressed people. Fluoxetine was marketed as a mood lifter. Fluoxetine supposed conveyed a positive attitude toward life. And who wouldn’t like to have that?

A turn around had been achieved with fluoxetine. Headaches pills are a part of daily life for many — but only to curb the pain. But a pill that provides you with a good attitude toward life — you don’t even need to be ill or be in pain. You can always take it. You could always do with a positive outlook on life.

Note: one of the original goals with the COVID-19 vaccines was to make them become an annual shot everyone took (hence guaranteeing the recurring sales which drive the pharmaceutical industry) and it is only because there has been so much pushback against this that the medical establishment has at last started to back off on that goal.

Prozac is Born

As an insider, Virapen had many insightful things to share about how Prozac was marketed:

“Flu-o-xe-tine” is difficult to pronounce, even more difficult to remember, and it sounds, if anything, like toothpaste. No, it had to be something trendy. The name was to be on everyone’s lips, within the shortest possible time. After all, that’s where the pills were going to go, too.

Eli Lilly paid a company, specializing in branding, hundreds of thousands of dollars to crack this hard nut... The company, commission to create the name, was Interbrand. The new pills, with the active ingredient, fluoxetine, were to be sold as Prozac. The name givers claim, and not without pride that this abstract name cleverly combines the positive association of “pro,” derived from the Greek/Latin with a short, effective sounding suffix.

Since that doesn’t sound quite as favorable in German as it does in English, the same active ingredient was marketed in Germany under the name Fluctin, as it sounds like the German “flutscht’s?” — Does it slide down well?

Note: I always found it ironic that this name was chosen since one of the characteristic side-effects of the SSRIs are the “brain zaps” one experiences when withdrawing from them.

Likewise, Prozac (and its successors) were sold on the myth that depression is due to a chemical imbalance (of serotonin) in the brain. While this was a catchy marketing slogan, it was actually never proven (e.g., CSF measurements of serotonin consistently disproved this hypothesis) and for years honest psychiatrists tried to protest against it. Fortunately, as more and more data has emerged which argues against the chemical imbalance theory, the psychiatric field has gradually moved towards identifying the (highly damaging) neural rewiring as the actual mechanism of the drugs (e.g., this explains why SSRIs often don’t work for the first few weeks of treatment as the brain has not yet rewired itself). I frequently cite this story to illustrate how speculative many of the mechanisms the practice of medicine is built around actually are.

Note: Eli Lilly was fully aware from the start that this was the actual mechanism of action of the drugs (as their scientists had discovered it in their research between 1975-1981).

The success of Prozac catapulted the whole family of SSRIs to the top of the best-selling pharmaceuticals. In 2006, the active ingredient, fluoxetine was still at number 18 for the amount of packages sold, although the patent for it ran out in August 2001. Let’s now take a look at exactly how Lilly (and the other pharmaceutical companies) did that.

Softening Diagnostic Boundaries

Prior to its approval, one approach Virapen used to market the drug was to conduct seeding trials where patients were recruited to “test” the drug — a tried and true method for making doctors who participated in the trials be open to prescribing the drug once it was approved.

That wasn’t bad — but not what we wanted to achieve. Fluoxetine was now being used in many clinics— but we weren’t much interested in the sick (if we supposed that people who visit a hospital for psychic problems or those who are referred there by force, are ill). The blockbuster is characterized by the fact, that it blurs the boundary between sick and healthy, that it is used uniformly, because only then can it achieve its extraordinary sales record.

Note: keep in mind how the COVID vaccines sales market kept on being expanded (e.g., to people who had already had COVID, and then to healthy children who were at no risk of dying from COVID, and then to boosting people over and over again).

When Lilly initially tried to get Prozac approved in Germany, it was rejected because they had concluded Lilly could neither prove what Fluoxetine actually did, nor could Lilly show which clinical picture Lilly was actually using to diagnose depression (as it clearly did not correlate to either Germany’s or the WHO’s definitions).

To “fix” this issue (and be able to sell to far more people), the pharmaceutical industry banded together to expand the definition of depression and over the years sponsored a variety of initiatives and patient groups to do so (e.g., England’s national “Defeat Depression Campaign” which encouraged general practitioners to treat far more patients for depression and aggressively do so with SSRIs). Many of these were spearheaded by “patient” groups, which were sponsored by the drug industry (this is another common sales tactic we see over and over).

Likewise, the industry also worked to formally expand the definition of depression:

Even amongst experts, the definition of depression isn’t clear. Attempts are being made to expel this vagueness by adding further definitions, but that doesn’t necessarily lead to clarity. The international standard is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association. The first issue of the DSM in 1952 had defined a good 100 distinguishable manifestation of depression. In the fifth edition (DSM-IV, 1994), the number of definitions had increased three-fold.

The major change in DSM-III from 1980 was the introduction of a symptom- based approach for diagnosis. It has been criticised for creating diseases and for classifying normal life distress and sadness as mental disease in need of drugs. Expected reactions to a situational context, for example the loss of a beloved person, divorce, serious disease or loss of job, are no longer mentioned as exclusion criteria when making the diagnosis. These changes, which are so generous towards the drug industry, could be related to the fact that all the DSM- IV panel members on mood disorders had financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry.

In case you are wondering how that came to be:

DSM IV is produced by the consensus of a group of psychiatrists. 56% of its authors had or still have financial connections to pharmaceutical companies, with 100% of those on the committee for ‘mood disorders’ and ‘schizophrenia’ having those conflicts.

In turn, a variety of normal behaviors have been relabeled as being pathologic, many of which the patient would never have noticed had they not been pointed out to them.

For example:

If you asked the people you know, “Do you sometimes feel one way and then another?” — Most will probably reply yes. Mood swings are completely normal. If you treat mood swings as a sign of depression, the number of people with depression increases to include [almost all] of the population.

Similarly:

In 2010, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated that 9% of the interviewed adults met the DSM-IV criteria for current depression. However, very little is required. You are depressed if you have had little interest or pleasure in doing things for eight days over the past two weeks plus one additional symptom, which can be many things, for example:

•Trouble falling asleep

•Poor appetite or overeating

•Being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual.

Pharmaceutical Sales Funnels

Much of business revolves around creating sales funnels where you initially start with an innocuous offer that can reach a lot of people, and then from that filter out a pool of people who can be sold a more expensive product, and then often repeat that process multiple times, allowing the large funnel to gradually get smaller and more profitable.

However, while this sounds fairly reasonable from a marketing perspective, once you mix it with medical products bad things can happen. For example, in a recent article, I showed how many patients with chronic neck or back pain, rather than having their pain treated, get fed into a sales funnel that results in them getting (incredibly profitable) spinal surgeries that typically fail to fix the issue and frequently leaves them with significant chronic complications.

One of the most depressing pharmaceutical sales funnels I’ve seen happens to young girls throughout America. It goes as follows:

•Young girls are told a variety of normal symptoms they are experiencing (e.g., painful menstrual cramps and mood swings during their cycle) need to be treated with birth control pills (which are also pushed on girls who might become sexually active).

•One of the common side effects of birth control pills are mood alterations (e.g., anxiety or depression), issues girls already struggle with due to the confusing changes in their body that accompany puberty and the challenging social environment our society raises its women in.

•Once those psychiatric side effects emerge, their doctors immediately advocate for treating them with SSRIs.

•Those SSRIs then cause a variety of other emotional problems (e.g., anxiety or bipolar disorder).

Note: certain other neurotoxic pharmaceuticals like the HPV vaccine (which is pushed on adolescent girls across America) can also create these issues or accelerate their progression.

•Those more severe psychiatric issues are treated with mood stabilizer and anti-psychotics, both of which are very powerful medications that frequently leave the individual with permanent psychiatric and cognitive damage.

I share this example because of just how many women I’ve seen have their lives ruined by it, and likewise how much this massive consumption of psychiatric medication has been normalized (e.g., many young adults now heavily identify with their addictive medications).

Note: after I posted this article, a reader shared a remarkable Moderna commercial I thought needed to be shared.

Screening for Depression

One of the most common sales funnels you see in medicine is a program being put into place (often due to pharmaceutical lobbying) to screen large numbers of people for a condition.

Some of these actually are quite helpful—for example the invention and mass implementation of the pap smear has saved a lot of women from dying from cervical cancer.

Unfortunately, many other common screenings don’t benefit those who receive them (e.g., Peter Gøtzche, one of the primary sources for this series whom I quoted throughout this article, also wrote an excellent book which proved that giving routine mammograms to women without signs of cancer is more likely to harm than help them).

Most frequently, mass screening programs are created to find eligible candidates to sell drugs to, and time and time again, you will notice more and more people become eligible for the drug. For example:

•The cut off for “high blood pressure” (which is measured at every medical visit) has been lowered again and again (to the point we now over-medicate the elderly who, due to an aging vascular system, need a higher blood pressure to supply the brain in turn frequently experience a variety of severe complications like falls from light-headedness induced by blood pressure reducing medications).

•Once an effective way was found to lower cholesterol (with the statins), the “normal” cholesterol level kept on getting lowered—which made a lot of money but also caused many patients to experience severe side effects from their toxicity.

•Many psychiatric diagnostic criteria have likewise gradually had their scope broadened. For example, bereavement (grief over a loss such as a death or divorce) in DSM-III was only considered to be a depressive disorder if you still felt bad a year later, while in DSM-IV it was shortened to two months, and in DSM-V (in 2013) it was shortened to 2 weeks. In turn, there have been numerous cases of children who felt distraught because they had just broken up with their romantic partner and were immediately put on an SSRI who then had a disastrous suicide—whereas had they simply been given a month to process the breakup, they likely would have been fine.

So as you might imagine, the pharmaceutical industry has concocted many different methods (using the infinitely flexible criteria granted by the DSM) to screen patients for depression and get them the (pharmaceutical) treatment they “need.”

One of the most memorable ones occurred in 2010 on WebMD (an “authoritative” website which comes up near the top of most health related searches on Google). WebMD featured a “free” survey (which I suspect was prominently featured on the website) that users could take to see if they were depressed. Eventually (since so many people were taking it) some of them figured out that even if you answered that you did not have any symptoms of depression, the survey always stated that you either had major depression or were at risk for it, and to consider calling a doctor right away. After this was exposed, the language was softened but still implied you could be depressed even if you had none of the symptoms.

Note: this is similar to a heart attack risk calculator doctors across America are trained to utilize (e.g., medical board exams ask about it and current practice guidelines revolve around it). After it came out, I noticed it almost always said the patient had a significantly elevated risk of a heart attack (or stroke), and that my colleagues would immediately use its results to push statins on their patient so they “wouldn’t die.” I was thus immensely grateful to learn that in 2016, Kaiser studied this by looking at the electronic health care records of 307,591 Americans and discovered that the calculator was overestimating the risk of a heart attack or stroke by between 5 to 6 times. As you might imagine, Kaiser’s results have not been incorporated into the calculator.

Sadly, while the WebMD example seems absurd, in real life, due to the wide definition afforded to depression, many who are subject to the various screening programs that exist likewise come up as “having depression.” This in turn leads to tragedy after tragedy (a few of which were documented by Gøtzche) where someone was put on an SSRI despite there being no valid reason to start it and that individual then committing suicide as a result of the drug’s side effects.

Note: one of the things that really bothered me about working in medical clinics which took insurance was that “quality” metrics would always be introduced that required us to do a “necessary” procedure (e.g., pushing a statin, screening for depression, or pushing a flu shot) on most of our patients. Since the penalty for not meeting those metrics was lowered reimbursements, administrators would often scold physicians who failed to meet them. Likewise, I believe one of the biggest issues with primary care is that so much of each (already short) visit is taken up by essentially mandatory things (e.g., those screenings or checking boxes for insurance reimbursement), that not much time is left to actually focus on what the patient needs.

To quote Peter Gøtzche (as he has done so much to expose the harms of misguided screening programs):

A notorious programme in the United States was TeenScreen, which came up with the result that one in five children suffer from a mental disorder, leading to a flurry of discussions about a “crisis” in children’s mental health.

The screening test recommended by the World Health Organization is so poor that for every 100,000 healthy people screened, 36,000 will get a false diagnosis of depression.

The Cochrane review on screening for depression recommends firmly against it, after having examined 12 trials with 6,000 participants. Nonetheless, the Danish National Board of Health recommends screening for depression.

Note: one of the common responses Gøtzche receives from psychiatrists when he tries to highlight that mass-screening for depression results in many healthy people unnecessarily receiving antidepressants is that it “didn’t matter because antidepressants have no side-effects.”

Two of the most unfortunate groups that are subject to mass screening are the elderly and pregnant women. In the case of the elderly, while some do suffer from depression, they are also quite likely to suffer severe consequences from the drugs.

With regard to SSRIs, a UK cohort study of 60,746 patients older than 65 showed that they led to falls more often than the older antidepressants or if the depression isn’t treated, and that the drugs kill 3.6% of patients treated for one year.

Note: one of the less appreciated consequences of SSRIs is their tendency to cause low blood sodium levels (they increase the risk of it by 2-8 times). This condition can be very dangerous as it massively increases the chance of dying in the hospital and the risk of death in the years following the hospitalization. Prior to the hospitalization stage, hyponatremia will cause dizziness, light-headedness and muscle weakness—which I believe is a key reason why SSRIs increase the risk of (often devastating) falls.

In the case of the elderly, this is particularly tragic because they frequently lack the ability to refuse a prescription offered to them or to recognize its negative effects, while the majority of doctors (who are not geriatricians) likewise cannot do so.

Note: one memorable study found that withdrawing older adults from all clearly unnecessary drugs (which averaged 2.8 out of the 7.8 drugs they were taking) reduced their risk of dying by 23% and of hospitalization by 18.2% (along with saving a lot of money).

In the case of pregnant women, it is particularly tragic because not only does it hurt the mother, but also (as discussed above) the child as well. This brief skit by Gøtzche illustrates the absurdity of those screening programs.

Everyone’s On It

As the criteria for depression has been loosened and the pills have been aggressively marketed to more and more people, the use of antidepressants (and the stronger drugs they feed into) in a just few decades has gone from a tiny minority of the population to almost 1 in 4 of Americans.

Note: this figure is partly due to a massive increase from COVID-19 (e.g., in just the year of 2021, the number of people on psychiatric medications increased by 20% nationally and by 10-50% depending on the state).

Many in turn have noticed this concerning trend. Consider for example this song by an English Pop Star:

Sadly, the psychiatric profession has not.

With such an approach to diagnosis, it is not surprising that the prevalence of depression has increased dramatically since the days when we didn’t have antidepressant pills. And there is a substantial risk of circular evidence in all this. If a new class of drugs affect mood, appetite and sleep patterns, depression may be defined by industry supported psychiatrists as a disease that consists of just that; problems with mood, appetite and sleep patterns.

[The Skyrocketing Use of Antidepressants] should make everybody’s alarm bells ring, but when the TV host asked us during a panel discussion how we could reduce the high consumption and expressly pointed out that we should not discuss whether the consumption was too high, Professor Lars Kessing didn’t reply to the question but said the consumption wasn’t too high because the prevalence of depression had increased greatly during the last 50 years.

I have listened to many pseudo-academic discussions where people [e.g., psychiatrists] have tried to explain why there are more depressed people now than previously. The usual explanation is that our society has become more hectic and puts greater demands on people. As far as I can see, we are more privileged than ever before, our lives are less stressful, social security is far better, and there are far fewer poor people. It is more reliable to estimate whether the prevalence of severe depression has increased, and psychiatrists constantly tell me that this is not the case.

Do Antidepressants “Work”

In the previous article, I cited a study which showed that doctors tend to perceive their drugs benefit a patient more than the patient does and much more than than the patient’s family. Since there are so many subjective metrics involved in mental illness, this is an area that is particularly prone to (conscious and unconscious) biases from either the patient or the doctor overestimating an antidepressant’s benefit.

This bias in turn is why we have placebo controlled trials. Unfortunately, while there is a good justification for them, in practice, these trials in reality simply reinforce the status quo. This is because independent parties can almost never afford to conduct those trials (they cost a lot of money), while the pharmaceutical companies that typically conduct them always find ways to cheat and get the result they wanted from the start

Note: in the last article I discussed how this was done (with the FDA’s tacit approval) throughout the SSRI clinical trials and likewise mentioned how a whistleblower disclosed that Pfizer’s trial was not blinded (which likely invalided the trial’s results), but after the FDA was notified, they did nothing except tell her supervisors (who promptly fired her).

Since the antidepressant’s margin of benefit is relatively small, I think it is helpful to look at a few studies that tried to assess if the same results were gotten when it was not possible to know who was receiving the drugs.

Hróbjartsson recently published another important study. He wanted to see to what extent observers who had not been blinded to the treatment patients received exaggerate the effect, and he collected all trials that had both a blinded and a non- blinded observer.21 He included 21 trials for a variety of diseases and found that the treatment effect was overestimated by 36% on average when the non-blinded observer assessed the effect compared to the blinded observer. Most of the studies had used subjective outcomes, and as the effect of antidepressants is also assessed on subjective scales (e.g. the Hamilton scale).

Many years ago, trials were performed with tricyclic antidepressants that were adequately blinded, as the placebo contained atropine. This substance causes dryness in the mouth and other side effects similar to those seen with antidepressants, and the trials are therefore much more reliable than those using conventional placebos. The mouth can become so dry on an antidepressant that one can hear the tongue scraping and clicking, which is an important reason that some patients lose their teeth because of caries. A Cochrane review of nine trials (751 patients) with atropine in the placebo, failed to demonstrate an effect of tricyclic antidepressants.

Note: Since SSRIs have significant side effects, these can be immediately recognized during the trial, making the “blinding” a farce. Furthermore, this has been a longstanding problem with numerous classes of psychiatric medications. For example, a 1993 paper reviewing this issue concluded “the time has come to give up the illusion that most previous research dealing with the efficacy of psychotropic drugs has been adequately shielded against bias.”

What does this translate to in larger studies?

An analysis of a prescription database showed that after only two months half the patients had stopped taking the drug. Nonetheless, the psychiatrists love the pills and often say they work in 70-80% of patients, which is mathematically impossible when only 50% continue taking the drug after two months.

The FDA found in a metaanalysis of randomised trials with 100,000 patients, half of whom were depressed, that about 50% got better on an antidepressant and 40% on a placebo. A Cochrane review of depressed patients in primary care reported slightly higher benefits, but didn’t include the unpublished trials, which have much smaller effects than the published ones.

In parallel with branding depression to the world, the pharmaceutical industry has made us forget how many of these conditions would naturally go away on their own:

Most doctors call the 40% in the placebo group a placebo effect, which it isn’t. Most patients would have gotten better without a placebo pill, as this is the natural course of an untreated depression. Therefore, when doctors and patients say they have experienced that the treatment worked, we must say that such experiences aren’t reliable, as the patients might have fared equally well without treatment.

Note: the most insidious thing about this is that in many cases, SSRIs turn a temporary psychiatric condition into a permanent one.

Who Benefits from SRRIs?

(besides the pharmaceutical industry)

While I typically find antidepressants do not help people, it is also important for me to acknowledge that in some cases, they do really help a minority of the patients who are put on them.

Specifically, I tend to find the following to be true:

•Typically patients have much better results if they are prescribed SSRIs by a psychiatrist than if they are prescribed them by a general practitioner (as the psychiatrist is better able to recognize who is a good candidate for the drug and simultaneously is more likely to recognize if a patient is having a bad reaction to the drug).

Unfortunately, to quote one review on this topic: “primary care providers prescribe 79%percent of antidepressant medications and see 60% of people being treated for depression in the United States, and they do that with little support from specialist services.” This, in turn, I believe in the primary reason why there are so many patients who are on multiple (often harmful) psychiatric medications.

•There are psychiatrists with advanced expertise in psychopharmacology who can get excellent results for their patients (including for otherwise difficult cases). Unfortunately, doctors like this are quite rare to find and typically expensive to see (as they run cash pay practices). Most importantly, they’ve shared with me that there are many patients they nonetheless cannot help, and for those that they do help, in some cases it is also necessary for them to utilize integrative modalities.

•Metabolic variations (which are often genetic) play a huge role in determining who will have a positive or negative response to an antidepressant.

•If there is an underlying issue (be it physical or non-physical) causing the depression, I find it is often a bad idea to treat the issue with the medications. In turn, I frequently find this allows the underlying issue (e.g., an infection or an abusive dynamic) to fester and worsen (which in turn frequently makes it much harder to treat the psychiatric condition caused by that unaddressed issue).

Note: a foundational principle within natural medicine is Hering’s Law of Cure, which states that “disease” first enters the body superficially and then goes deeper into the body (or the mind and then spirit) as it worsens. Hering’s Law hence argues that the correct way to treat many illnesses is to encourage their superficial manifestations (symptoms) so it can exit the body, rather than suppressing them (which is what much of modern medicine does).

In turn, many remarkable historical examples of this exist. For example, early medical journals consistently reported giving aspirin to suppress fevers significantly increased the likelihood of dying from the 1918 Influenza, and I strongly suspect that the observations of the pathology of the smallpox vaccines (and how that was successfully treated) played a key role is developing this law.

Likewise, throughout my career, I’ve seen many tragic cases that remarkably embodied Herring’s Law of Cure. These include cases where some type of emotional or spiritual process was trying to express itself, which was then treated with (progressively stronger) psychiatric medications, which both suppressed but simultaneously intensified and worsened the underlying process.

Treating Depression

One of my longstanding beliefs has been that “no industry (or group) can be relied upon to solve a problem if it benefits from the problem continuing.” This encapsulates the idea that we have many parties who have been tasked with solving an issue (and often being given a lot of money to do so) but they completely fail to do so. Rather each year the issue becomes a bigger and bigger problem, which the groups in turn use to plead for urgency to receive more money.

Note: everything said about “money” here also applies to “power.” For example, many political groups exist which continually exaggerate the extent of an existing problem in order to gain more political capital due to the “danger” that problem poses.

In this article, I’ve tried to illustrate the terribly sad SSRI saga which to review went as follows:

•A bad drug was designed by a pharmaceutical company desperate to make money.

•Since that drug was too bad to be approved, a variety of unscrupulous approaches had to be used to get it onto the market.

•Once it started being sold to the public, its manufacturer realized the drug tapped into one of the most profitable markets in existence

•The manufacturer hence decided to do everything it could to convince as much of the population as possible that they were mentally unwell and “needed” this new drug.

•The rest of the industry realized this was a gold mine and jumped in, before long making so much money be behind the SSRIs that the drugs were protected by almost every institution on the planet.

In turn, our society’s relationship with depression has been transformed, as we have pathologized the normal ups and down of life, left countless individuals with permanent emotional dysfunction from these drugs, and prevented people from considering what is actually causing their unhappiness or how to address it.

At the same time however, for some people, depression is a very real condition they struggle with daily and which they do not get the needed help from the medical system to address. In looking at this dilemma, I’ve found the following factors seem to appear again and again:

•Giving a blanket label of “depression” to those conditions, while helpful for research and drug sales (since it makes it possible to cast a wide net that can show something reaches statistical significance in “treating” depression) does an immense disservice for “depressed” patients. This is because there are very different manifestations of “depression,” which often require very different types of management—and to that point, I must acknowledge that for the correct type of depression (which does not comprise the majority of cases) SSRIs are actually very helpful.

•There are a variety of different causes of depression. If you can identify the applicable cause, this can inform you of which treatment is most likely to help (or harm). This is important because there are a variety of treatments which do really help 10-25% of depressed patients, but when those treatments are utilized, it is almost never considered if they are being matched to the patients likely to benefit them—which in turn forces patients to go through a variety of treatments until they find the one that matches them.

•Because of the emphasis on (monetizable) pharmaceutical treatments for depression, many critically important non-pharmaceutical models of depression have been largely ignored.

In turn, I would argue that many of the challenges with depression ultimately from the fact a variety of symptoms which correlate with being “unhappy” (e.g., insomnia, low energy, poor sleep, anxiety) are all lumped under the single label of depression. In reality, each of these symptoms is often representative of different issues within the body and I believe that if doctors were trained to view each psychiatric symptom as having a specific meaning tied to it (rather than being folded into these broad brush strokes) it would often become possible to determine what the root cause of a patient’s unwellness is (as opposed to it being deemed “depression” and just treated with an antidepressant).

Thus, I feel that since I’ve criticized almost every aspect of the current approaches towards depression, I am also obligated to put forward the approaches I believe should be take their place.

Note: many pharmaceuticals have neurological toxicity and can trigger mood alternations, so it also always important to consider exactly what drugs a patient is on and if they started one prior to the current psychiatric symptoms emerging.

In the final part of this article, I will share my perspectives on how to address the various types of depression and that of my colleagues who frequently work with it (which includes both affordable and somewhat expensive treatments).

Note: for ease of reading, I have also included an early-release of a detailed review of the evidence behind which non-pharmaceutical treatments help for depression that can be referenced for more information on a specific topic. Since it has not yet been publicly released, please do not share it until it has been.